When Productivity is... Agile?

Last Updated: 2022-09-08In an effort to make productive use of my spare hours during the day, I have increased my reading over the last year. Not only of general topics (science, history) and fiction, but also self-improvement, both a mix of classic stoicism and modern self-improvement.

One of my friends offered me the book 'Help' by Oliver Burkeman, which appealed to me because I'm a sucker for books which distill a lot of information into some informative summaries. The book itself was a mixed bag (you can read my review of it here), but I found myself highlighting quite a few passages, and I could feel that some of them were somehow linked together in an interesting and familiar way.

I now present a list of productivity tips to you below which I feel had the most impact, and their surprising association.

On Tip-Lists

Lets start off a little meta: what really is the benefit of a tip-list? And yes, the irony is not lost on me. I'm sure that most readers of this article will have obtained some kind of tip-list in some form or another. It's in our nature, mainly because we find it easer for people to dispense advice to us than eliciting it from ourselves, but I think we all have some kind of desire in us to improve ourselves somehow.

Burkeman does cover the topic of tip-lists in his book, and wisely warns us of mistakenly "obscuring the advice we need with the advice that we enjoy", which I think is a quote worth remembering. How quick are we to open a book, email or link for a list of tips simply because we enjoy getting tips? Some advice that we read may make us feel good by only serving our ego, rather than our success.

So be wary of tip-lists, and make sure that they are worthy of your time and effort, that they will genuinely benefit you. But I promise that this particular list is a good one.

Regret

"We approach decisions, big or small, burdened by the fear that whatever the choice we make, we will come to regret it". Burkeman paraphrases this from philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. The original quote is somewhat more depressing:

"Do it or do not do it. You will regret both."

Yikes.

A more generous way of looking at this is that these two instances of regret are not equal; we may regret a choice we made to do something as it perhaps uses up more of our time than we thought, is not as successful as we thought, or is more difficult than we thought, but according to studies conducted in this area, the regret of having not made the choice in the first place is usually greater and lasts longer. As Burkeman summarises: "we habitually believe we'll regret acting more than not acting, when the opposite is true".

Picture yourself at the top of a bungee-jump. You look down over the edge to the ravine below and imagine yourself falling, one of the most unnatural feelings of lack of control; you feel your heart racing, your skin tingling, your adrenaline surging. So you step back and pull out. Your friend steps up and does what you didn't. Later, reflecting over a beer, you feel the lingering regret of having not gone through with it. You ask your friend "Do you regret jumping?". I think you know what the answer would be.

What should you do instead? Just do it, take the leap. While a bungee jump is probably not a good analogy for this paragraph (because once off the ledge you actually have no control), you should try, evaluate, learn and adjust. Whatever you are doing is likely to be difficult and challenging, but perhaps this is mostly down to lack of information or vague assumptions, which can be corrected or improved. If it does end up as bad as you thought you can always pull out, but still wiser.

The Two (or Three) Minute Rule

A short and sweet one. If something is going to take less than 3 minutes (Burkeman says 2 minutes, but I think the rule is significant enough to stretch a bit), just get it done straight away. Don't put it off, don't put it on a list. Do it now. You will be amazed how lighter your overall list (see below) will become without those 3 things that you just knocked off in 10 minutes.

As a corollary to this and the previous tip is the quote from G. K. Chesterton, which I feel is often misunderstood:

"If a thing is worth doing it is worth doing badly"

As Burkeman points out, some important things are often over-analysed and over-planned to the point that their importance is lost and they are discarded. If something is important enough to be worth doing, don't fuss on the details. Don't do it perfectly, just get it done. You can tweak and improve later.

To-Do Lists

"The notion of dedicating time to time-management [is] perverse" begins Burkeman in this section. I can see the irony. But I am one of those people who can't seem to get by without a to-do list. Whether it be simply for capturing tasks to prevent them slipping from my mind, for prioritising amongst other things or for the cathartic joy of simply ticking things off (and sometimes writing things down for that sole purpose... go on admit it). It is here that the dichotomy of the to-do list comes into play. Burkeman points out that these lists are often the source of conflicting feelings; one of control that you are on top of the things you need to do, and one of anxiety when you fail to finish everything you have listed.

So what are we to-do (pun intended)? Burkeman provides 3 good tips:

- By all means, keep a master list of everything, but don't work from that list. At the start of a day, identify what you are actually going to tackle. Set yourself a reasonable target and put those on your list for the day. By giving yourself something achievable, you are setting yourself up for a good chance of success, and thus removing the anxiety of having a half-finished list at the end of the day.

- Make sure your lists are "will-do" and not "to-do" - remember the tip-list trap. The lists (especially the daily list) should be things that are necessary to achieve and will get done, not things that you simply feel like doing. The transfer from master to daily offers you a good opportunity to evaluate which are the necessary tasks.

- Your daily list should be 'closed', in that it is not to be added to during that day. Put any new tasks on your master list, as well as those that you didn't quite knock off at the end of the day.

I started using these tactics a few months ago and I was surprised to find them so helpful and effective. With a smaller daily list, I improved my chance of finishing what you set to do which did give me a boost when I finished them all, which then carried over to the next day. It's also more meaningful to reward yourself at the end of the day when you have an empty list. Even if you don't finish the list there is likely to only be one or two things left, which does not feel so defeating. Daily lists can also be adjusted around chores or appointments you may have during that day, which means you can be more realistic about what you can achieve.

As I was populating my daily list in the morning, I found myself looking over what I had achieved on other days in order to determine what I thought I could achieve today, which was a very familiar thing. I started to wonder what other tips might give me the same feeling.

The Planning Fallacy

As mentioned above, working off a giant master list all the time is futile and simply adds to your anxiety, which is carried forward to the next day. Equally, as Burkeman notes "the list-makers among us get up each day and make to-do lists that by the same evening will seem laughable". At this point he quotes the most amusing Hofstadter's Law, which claims for any task:

"It will always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law"

You may mirth, but it you have an office job I suspect you are only laughing on the outside.

Hofstadter's Law may be (superficially) amusing, but we are intelligent human beings, are we not? Well, it seems not; this is the 'Planning Fallacy' - we know that everything always takes longer than expected, but we just seem to forget whenever we plan something new.

Burkeman's advice comes from author Eliezer Yudkowsky - avoid the traditional method of subdivision and going into detail. The most accurate estimates (at least for small-scale stuff) come from comparing against similar tasks that have gone before. Where possible, simply avoid planning and use a 'ready, fire, aim' approach, correcting your course as you go along.

I also applied this method to my to-do lists, but in order to do so I kept a track of the 'size' of my tasks and how many I could fit into one day. With this minimal effort, I was able to to reliably predict how many things I could do in a day. Wow, I thought, this is great... and just like the To-Do list tips, I also thought I had seen something like this before.

Effective vs Efficient

I'll keep this one short; as you may have heard before, efficiency is not the same as effectiveness. This has already been suggested under the To-Do list tips, but it is worth elaborating. Efficiency comes with keeping busy and doing many things; effectiveness is making the most of your time or adding the most value to your day in a focussed manner. After you have completed your list at the end of the day, it may make you feel good, but are you now in a better position than you were in the morning?

This is an important filter that, as mentioned in the To-Do section, can be applied to your daily list as you create it; you know what your goals and priorities are, so what can be done today that will have the greatest impact on them? Similar to the tip on Tip-Lists, one serves our success, and one serves only our ego.

All In A Nice Bow

You may have noticed that many of these things are interlinked in some way other than just being about productivity. Depending on your background, you may also have noticed a familiar thread woven through these tips as I did. What is it that is familiar about:

- maintaining a master list and a daily list

- ensuring your chosen tasks are the most valuable

- tracking your previous productivity to forecast your future productivity

- trying, evaluating, learning and adjusting

It struck me enough that against several highlights I made in the book I simply wrote 'Agile!' in the margin; these tips all share philosophies found in Agile thinking and also key techniques found in SCRUM.

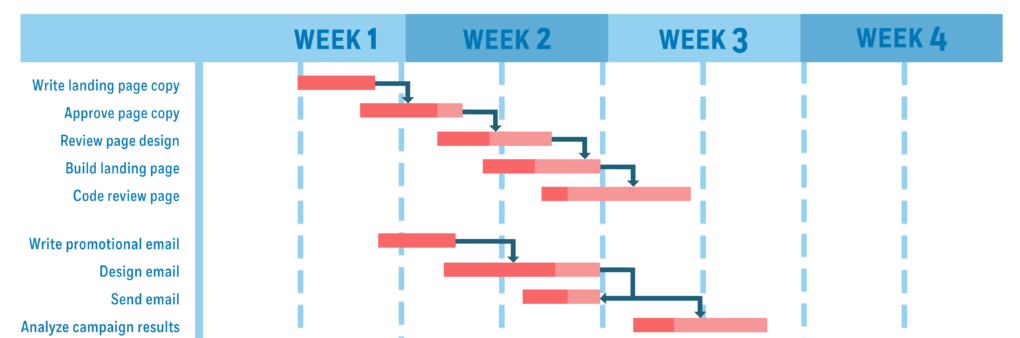

- a master and daily list mirrors SCRUM's backlog and sprint log

- selecting the most valuable tasks is akin to backlog prioritisation and task selection in a SCRUM sprint planning meeting

- productivity tracking and forecasting is just like story points* and team velocity

- trying, evaluating, learning, adjusting == MVP, experimenting, measuring, pivoting == Agile thinking

*I had a major epiphany upon this realisation which I will write about later.

My success in adopting these methods not only re-enforced what I have learned about Agile-type methods, they also served to clarify some of them. SCRUM is designed to help navigate teams through complex systems and tries to dispense with detailed up-front analysis in favour of prioritizing, measuring and adjusting. As Burkeman even says in this unrelated book "the problem with unforeseen delays is that you can't forsee them"; SCRUM admits their presence and does its best to manage them. You can read more about this in my SCRUM post

For Success

Hopefully these tips will also be useful to you in general, and if you work in software, they will also add some extra clarity as they did me. There are more passages that I highlighted in this book, including interesting perspectives on passion, systems and loneliness, but these were the ones which were most coherently tied together.

I will leave you with one final tip which stuck with me. The tips listed above are not extreme, complicated or revolutionary; they are simple and easily implemented, and chances are that you already do one or two of them. Equally, Burkeman advocates in one section against taking extreme measures; they are surely difficult to adopt and will only be sustained with a great effort that most of us don't have. Instead "choose a moderate goal and stick to it with an extremist's zeal". It seems to be working for me; select a few new habits which are not too hard to adopt, but adhere to them mercilessly. I've seen the change and I think you will too.