On Technical Debt

Published: 2022-10-27Back in the late-noughties, the phrase "Technical Debt" crept into my workplace. I was leading a team writing safety-related railway-control software - there were many very smart people on the team, so not only did I perk up when I heard this new term, it was also simply a very catchy phrase:

"Technical Debt".

It seemed to sum up and encapsulate many of the problems that developers talked about.

But as with many things discussed around the water cooler at the time, I think it was misunderstood. Just like the new hotlist of words that were also creeping in to conversations: Agile, Scrum, TDD, Units. In hindsight they tended to be overheard, interpreted and then "implemented by assumption". So what about Technical Debt? As a developer myself I instinctively attached attributes and context to this new phrase, some being right and some being wrong.

Why is Debt Bad?

In our everyday lives we use the word "debt" in a negative way. "I'm in debt", "drowning in debt", "need to pay my debts". Debt is burden. But is it really bad? Consider this, if you go and borrow some money from a bank, probably to buy a house or a car, do you walk out of the bank and then tell your family and friends that you are "in debt"? I suspect that you don't; instead you will say "I've bought a house!" and start planning your house-warming.

The best analogy to debt I have heard is that you are "borrowing against the future". You are banking on the fact that something beneficial will happen, and paying an additional cost (interest) to enable that thing to happen. In most consumer cases it is a mortgage - you pay a fee to the bank to enable you to own a house now rather than in 10-15 years time and also hopefully to benefit from it gaining in value.

This "gain in value" is key: In David Graeber's amazing (and considerable) book "Debt: The First 5000 Years", he opens with the point that "Consumer debt is the lifeblood of our economy. All modern nation-states are built on deficit spending." This basically means that you often need to borrow to get ahead. This is what any business loan enables: the business owner considers it will be favourable to borrow money so that his business income will out-strip the cost of his debt and give him something that otherwise he could not have had.

Of course Graeber is referring to "good debt" - debt that is intended to generate value and is expected to be paid off. If you borrow simply for indulgence or frivolity with a high risk of not being able to repay, then this is "bad debt".

So where does that leave this phrase "Technical Debt"?

Technical Borrowing

The driving force behind Agile and Scrum is, coincidentally, the market. The market is the ultimate litmus test of a business or product: achieve 'market fit' and you will be rolling in customers' revenue; "Miss the market" and you will be quickly forgotten. Agile seeks to address the assumption that your product has an immediate market fit, and that it simply has to be built. Instead, finding the fit is a bit like a game of "Wordle": after your first guess at least, you have some pretty good knowledge about what the answer is, but at each turn you need to make some adjustments. We should expect that most new businesses have the general gist of where their perfect market fit is, but they still need to wriggle around a bit to find it.

In this paradigm, the first throw of the business dart is the MVP. Agile and Scrum encourage you to get an MVP out as quickly as possible to get early feedback from the market, and in order to do that you need to make some swift decisions about your technology. Speed and adaptation is of the essence, and so you borrow against the future - you pay a cost, that being a sacrifice of a design choice or 'polished' code, to get out your MVP. Then you find you need to change, and to do so quickly you borrow again and again. But the result is that you find your way to a great market fit.

Some time later your developers start complaining about "spaghetti code", "high coupling" and "fragility". These things can of course be bad, but if you agree that it was a worthy cost (or interest payment) to enable your business to thrive, then you have successfully borrowed against the future.

So what exactly is it that you are borrowing? You are generally borrowing from the "-ilities": flexibility, testability, maintainability. In return you are getting what any "good debt" should generate - additional value. The key problem is paying it back.

Types of debt

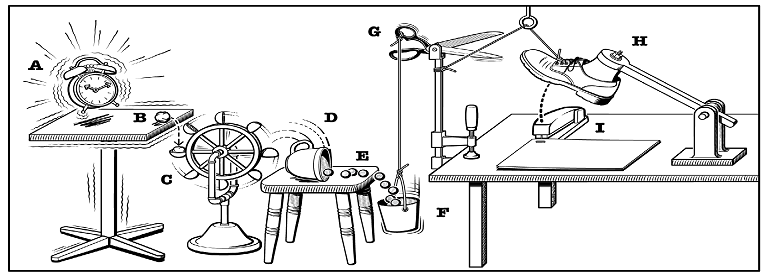

In a paper from 2008, Steve McConnell splits Technical Debt into 2 types: unintentional and intentional. Unintentional debt is the kind that is incurred, as suggested, without an intention to do so. Examples are code written by junior programmers, or maybe when testing practices were immature. Intentional debt is that which I have described above: an organisation makes a conscious decision to "optimise for the present rather than the future". This is the same as "borrowing against the future" because we expect that the future will either hold some benefit, or will not exist at all without this decision.

McConnell also breaks debt down into short-term and long-term debt. Short-term debt is usually incurred by market pressures and may be manifested as corner-cutting or "unpolished" code. Long-term debt is more strategic in nature and my be manifested as design choices influenced by market size or product diversity.

With the recent increase in SaaS, PaaS and other service offerings, as well as an increased celebrity of shiny tech-stacks, I think there is a third type of debt, a kind of inverse-debt where choices are seemingly made on the best interest of the technology but at the expense of value to the business. For example I have talked to organisations that are running Kubernetes for only 2 containers with most of the features (including auto-scaling!) turned off. I've also heard new projects being designed with microservice patterns from the start before knowing how many services there are likely to be (if even more than one). Dave Farley has an excellent video on micro-services and the hazards of going down that path.

This type of debt borrows in a very different way and goes against agile and lean principles: you are likely to be borrowing against time and money at the expense of value, and this can be very bad for small and growing organisations. Even for companies with healthy budgets where it does not seem like "borrowing", it can still result in sacrificing important feedback about value and the ability to adapt. Because of this I classify it as "bad debt".

Interest Payments

In keeping with the analogy with financial debt, McConnell goes on to state that "If the debt grows large enough, eventually the company will spend more on servicing its debt than it invests in increasing the value of its other assets." This is when debt is a problem - the effort in servicing your debt is doing damage to your ability to generate new value. When Ward Cunningham explained his 'Debt Metaphor', he said that the things that you learn when you push software out early should also be re-invested into the software, and if you don't you will simply be paying interest forever.

This aligns with lean/agile/Scrum principles, since this debt-servicing should typically be considered as waste. I don't believe it is complete waste as some activities are, because the servicing of this debt may still be causing your business to be profitable. But if you are unable to generate new value effectively then you will be come stagnant in the market and allow competitors to move past you.

As I have mentioned in other articles, Scrum is designed to help you to reveal this issue and to keep on top of it. If this constant servicing is causing team velocity to fall, then there is clearly a problem and it needs to be addressed. Scrum also provides built-in events and actions to ensure that these corrections can be made, and they need to be made so that you don't end up "drowning in debt". But Scrum also reveals where your highest future value lies, which is in the priorities of your backlog. There may be technical debt lurking in other parts of the system, but that is not where new value is being created. In this case it won't be revealed, and it is probably perfectly fine to leave it alone.

"Bad Debt" also incurs interest. Over-engineering and poor design or platform choices will require additional costs and effort. In one conversation I had with a tech business owner, he described how whatever benefit they had gained from running a Kubernetes cluster was now outweighed not only by the extra staff required, but of the extra costs in hiring staff with the appropriate skills. Choices like these may be much harder to undo, and so prudence and foresight in this critical decision-making is necessary.

Forgiveness

We should also be conscious that some debt can be forgiven. Consider the module written at the start of a project: developers probably hate it, the author has long since moved on and no-one really knows how it does what it does. The loudest voice in the room says "re-write!".

At this point you should slow down and ask a few questions... how often does this module need to be updated? Is it a cause of failure? What is the actual cost to the business? How long will a replacement take? What value will it add and what functionality will risk being lost in translating it? As with a lot of 'mature' code, it is very likely that it is full of (unfortunately undocumented) bug fixes and IP details. There are always trade-offs, and once again your Scrum mechanisms should be mature enough to be able to make an informed value vs effort decision.

Choosing Debt

Debt is not a bad thing, but like real-world debt it must incur a benefit and then be managed away. In a 2009 comment, Martin Fowler says that "The point is that the debt yields value sooner, but needs to be paid off as soon as possible".

Whenever you make a business-influenced decision that makes you feel a little uncomfortable technically, you are probably incurring debt. It is up to you to first filter whether this is good or bad debt, ensure that it will yield value, and plan for paying it off. You also need to keep on the lookout for the "unintentional debt" - the regular Scrum events and the quality of the team and their practices will help with this. Both of these are also a type of shift-left thinking, and perhaps with experience they can be shifted a little more. But don't be afraid to borrow if you need to.