Interview: Nick Jenkins On Lean

Published: 2023-03-09Mechanical Rock started off as a small cloud consultancy in Perth, Australia, who approached me when they had perhaps 10 or so employees. Only a few years later, they had over 30 people, some of the biggest Australian banks and mining companies as their clients and were AWS and Google partners. Nick Jenkins was a company director on that journey, and previously held leadership roles in large companies such as Optus Mobile and BankWest.

I knew Nick had a passion for Lean, but while we worked together there was rarely an opportunity to talk about it. So when he announced he was moving on to other things, I guessed he would have a little spare time to have a chat and reveal a little more about it. Below are the Lean-related extracts of our conversation.

Lean Misconceptions

DDD: So we're going to talk a bit about Lean. I for one have found over my career, and it's become more clear in hindsight, that the phrases and names of techniques for a concept are often taken out of context or interpreted without reading the actual background material. Do you see this also happening for Lean?

Nick Jenkins: That's an easy one. So Eric Ries and "Lean Startup" is the most damaging one. Lean has its history in the Toyota Production System, and a couple of guys who actually went and trained in Toyota and came back to the States and did it in the States. And they wrote a paper, it might have been the 50s or the 60s, where they calling the phrase "Lean". And they both say now, it was an awful, awful term, but they had to call it something and it stuck. The first people to co-opt it were actually the 6-Sigma bunch, because there was a fad for 6-Sigma after Jack Welch and GE. But what people found was that it actually 6-Sigma itself is only very useful in a very narrow field. But the most popular corruption of Lean is "Lean Startup" by Eric Ries. I think the story is he looked at Amazon and that's where he got a lot of his ideas. Both the DevOps movement and Amazon have a root in people who understood Lean, and somewhere in there is the genealogy of Lean ideas. But Eric basically summarized it and turned it into a popular format to get rich, and everybody lapped it up.

Value

DDD: If you read Lean literature, the definition of "Value" can be written very simply, but how complicated is it to actually detect? Some things may be associated with value with some very simple metrics and others might not be.

NJ: One of the reasons that Lean hasn't been as popular as Agile or as Lean Startup or even 6-Sigma is because it is somewhat inscrutable. So the concept of "Value" is central - the definition is basically that it's what a customer will pay for. It's not actually that hard to detect the value, what is really hard to detect and measure is what contributes to the value and what doesn't. So that's the concept of value and waste. It's actually very easy to measure in a process, it's called Process Cycle Efficiency, or PCE, and it's basically the proportion of time that it is value-adding versus the proportion of time that is not. But of course, this is all taught a very inscrutable Japanese way. The traditional way of teaching somebody to see value and see waste is called "developing eyes for waste".

The story goes, they used to do this thing in Toyota where you get a new engineer who will be responsible for some part of the process, and they walk out onto the factory floor with them, draw a circle on the floor and say, "Stand in that. Watch what's going on. Don't leave the circle. I'll be back in an hour." They would then come back and go, "what did you see?" And the new guy would say, oh, well, the stuff goes from here to here and goes out the other side and blah, blah, blah. And the manager would say "you've learned nothing". So they would walk away and come back in another hour and go, "now what do you think?" And this kind of goes on and the idea is that you sit there and you look at a process and you need to understand what's value-adding and what's not. So it is quite a difficult concept. But once it kind of latches onto you and you start looking at things, you understand that generally as a society, we are very, very inefficient. People have done stats about it. The Process Cycle Efficiency Toyota is up to about 30%, I think in the best factories, and that is after 70 years of the Toyota way. In other industries, like healthcare and construction, you can get to about 10%. But then when you get down to service industries like IT or the bulk of western economies, it's less than 1%.

Improve and Empower

DDD: One thing that very often happens in organizations, especially growing organizations, is choosing to do things a different way and experimenting with new methods. But how difficult is it to actually detect if this change is going to add value? Is it worth having that discussion, or is it better to simply detect waste early and act quickly?

NJ: There's a very obvious tool to do it that we've had for several thousand years, that most people don't understand and don't use, which is the Scientific Method. The heart of process improvement in Lean is incremental improvements. You can do Big Bang, "Kaizen" is the word, but 90% of the improvement is done by the workers doing the work in the process of work. One of the phrases that's come out of the DevOps movement that I really like is "elevate the improvement of daily work over daily work". And it takes people a long time to get that one, but it's absolutely right.

Years ago, I went on a Lean tour in Melbourne to a conference and we did three case studies and one was VistaPrint. VistaPrint print about 90% of all the business cards in Australia and also do t-shirts and that kind of stuff. They were going for a thing called the "Shingo Prize", which is like the Lean Olympics where you have to demonstrate year-on-year improvement over X years. We went into the factory and talked to them and they were doing enormous amounts of work with an incredibly small number of people. Somebody asked, "how many improvements have you done so far this year?" and without missing a beat the operations manager said, "oh, we're on track for about 65,000 improvements this year". And it sounds like a lot, but then when you do the numbers, it turns out to be one improvement per worker per day.

As an example of this, they have packing stations where everything comes off the various printing lines and then somebody's got to put it in a box and slap a label on it and send it off to the shipping dock. These stations have screens and things and lots of tape and glue and all this kind of stuff. We went past one and there were two girls, and one of them was putting the stuff back on shelves and the other one was videotaping it. So we talked to them and said "What are you doing? Why are you videotaping?" And they said the setup and teardown of the workstation is really important because it dictates the process. We have a night shift in the day shift and we used to write-up [workstation changes]. We used to have like a glossy sheet and we draw on it for changes. But now we're making so many changes to the layout of the workstation that we just shoot a video for the next team who would watch it and see if it works. So the key to it is just the scientific method: form a hypothesis, then decide how you're going to test it, test it, decide if it passed or failed, and the only addition in Lean is the final step, which is if it passed, make it part of the standard operating procedures. And just keep doing that.

DDD: So what you're saying about breaking 65,000 improvements down to a per worker per day, that seems to be empowering the people to improve their own job, which is also one of the tenets of Agile and self-organizing teams. I'm interested to know, especially working reading essays such like David Graeber's "On Bullshit Jobs" and things like that, how much of an impact this kind of thinking has on the middle management layer and how much inertia that is going to take to change?

NJ: It's massive. So there's a guy called John Shook, who is one of the original guys, and I had a privilege of hearing him speak, he was inspiring. He talked about Lean and he said, one of the purposes of Lean is to give meaning to ordinary work. You know, to let people own their own job and actually get value out of it. And one of the ways you do that is by letting them actually do a good job. Instead of trying to impose a whole bunch of constraints on them and pretend that you know better than they do, just actually let them change the environment to do a better job. The role of the middle-manager, then becomes kind of a teacher, which is: you can't teach them to do their job better than they already know, but you can teach them to problem-solve. And so things like the scientific method in a practical sense, not in an academic sense, is how do you teach them to do those experiments? So it does really change the nature of middle-management.

Teaching and Thinking

DDD: Lean seems to operate best when you kind of ingrain it into the organization, but a consultancy like Mechanical Rock deals with many organisations. Did you manage to actually implement any Lean strategies with any of the clients that you engaged, or was it really only operating at the Operation level of the consultancy?

NJ: So within organizations I've led, but also within clients, you get two kinds of people. You get the ones that want the results, and then you get the ones who want time to understand. And a Lean consultant I knew described this a long time ago, he said he never confuses the two. For the ones who want to understand Lean and really embrace it and stuff, it's a ten year journey. It's just what it takes. The ones who wants the results you don't even bother trying to tell them. So whether it was internally or I was talking to clients, there was always a flavor of Lean. There was always elements of it there. There was always the language. So somebody would ask us to do a review of their development process, and I would use words like 'value' or 'value-add' and 'value-stream', even potentially things like process cycle time. Not many of them actually took it to heart and said, 'I want to learn this stuff'. But interestingly, some people do. I had coffee literally this week with a guy who haven't seen three years. He works around the mining companies in Perth doing IT stuff. And he's very, very smart, very driven, wants to be a CTO at some point. After a bit of a sabbatical he then came back to a new team and decided to play with some DevOps and some Lean ideas. And he said, he got to the point where yesterday he was in a meeting, and between answering questions, he shipped a release, and that used to take about three months. And furthermore, it just works. It never breaks. And if it does break, it's a ten minute rollback. And I said, so what stops you doing that before? And he said, I just didn't have the time to think about it. So it does stick and people do adopt it, but one thing I've learned over the years is I can't force it on people; I can't persuade people, I shouldn't try, I just talk about it.

Books and The Future

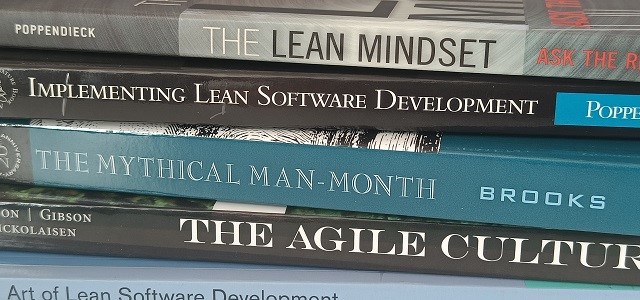

DDD: So I certainly found a lot of value in going back to the source material for Scrum, to actually understand the decisions that were taken to make Scrum what it is and what problems it was actually trying to address. Are there any particular books you would recommend for people wanting to understand Lean?

NJ: I have probably a linear metre of Lean books! So obviously in the world of DevOps and software, it's the Gene Kim books of various descriptions. But the first one, which is very old, is Deming's "Out of the Crisis." It's actually really good and I go back to it for all kinds of things. The misattributed quote [from Demming] is "you can't manage what you can't measure". The actual quote from Demming is "it's a costly mistake to think that you can't manage what you can't measure". So a 180° reversal. He talks a lot about using statistical measures in the right place and using human measures in the other places. So he's really good. So that's the roots of Lean. And then we get the Lean stuff, the lightweight Bible is probably "Lean Thinking" by Womack and Jones. That's not too bad. The one that got me started, though, was actually "Chasing The Rabbit" by Steven Spears. It's also called "The High Velocity Edge" in a newer version. It's a very, very broad book and one of the things he talks about is becoming a learning organization. And there's a lot of weight to that, and it's based, basically, on Lean.

On the IT side, my favorite ones pre-Gene Kim, is the Poppendiecks. Mary was a 3M engineer who worked on some very big things and understood Lean because it comes from the same kind of engineering manufacturing background. I got involved in some agile projects way back around the time of XP, and I wasn't impressed. And then I went away and I came back, years later, and it had changed, it had a whole bunch of other stuff in it and a lot of it came from Lean. And it was a precursor to DevOps. You could see that people had gone back to the source and thought about it and had managed to translate the concepts into Software Engineering. So I guess Mary was one of the first and then Gene [Kim] came along and did an even better job of not only translating the message, but translating the techniques to figure out what it meant to apply Lean and that's where we got DevOps.

DDD: Is there anything else in the future for Nick Jenkins? Maybe even in the Lean field?

NJ: So one of the lessons that Lean taught me was I couldn't leave my past behind. So I ended up doing Lean in IT because I know about IT and I knew about Lean. I tried to do Lean in other industries and they didn't want it, frankly. So I'm actually hoping that there's a real intersection between urban planning and town planning [which I'm now studying] and Lean and IT. I think there's probably going to be a combination there. And I think there should be a lot of stuff around being data driven, which is very Lean idea, but also identifying where the value is and then using IT systems to automate away the boring non-value-add stuff. So I'm thinking that maybe somewhere there, there's some kind of insight into what value in urban planning is. And then there's some insight into how you get there quicker, because that seems to be a major problem.

DDD: Great, well thank you Nick!

Nick Jenkins is a consultant and a writer who is interested in how people live and work with technology. He grew up frolicking with kangaroos on the banks of the Swan River in Perth, Western Australia and has worked in London, Sydney, Boston and Prague. He is a lifelong student of Lean and the Toyota Way and a passion for helping people find value in their working life.

You can find Nick's Blog here.

Book links:

- Out Of The Crisis / Demming

- Lean Thinking / Womak and Jones

- Chasing The Rabbit / Spears

- Leading Lean Software Development / Poppendieck